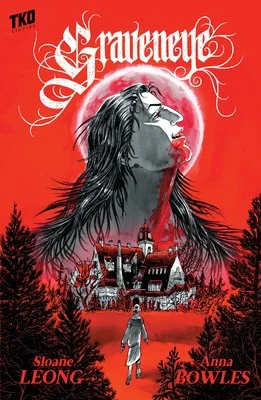

Hot Off the Shelf: Graveneye by Sloane Leong and Anna Bowles

[image description: The cover of Graveneye, which features a large mansion surrounded by trees and a gangly woman walking toward the house. Looming above the mansion is a feral-looking woman with blood splattered around her mouth and throat.]

Disclaimer: I received a free copy of Graveneye in exchange for an honest review and I honestly enjoyed it!

Post contains an affiliate link.

I’ve been on the hunt for a good creepy graphic horror novel since I finished The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina (which was a comic series before it was a TV show), so I was thrilled when Graveneye by Sloane Leong and Anna Bowles arrived in my mailbox.

First, the synopsis:

Isla’s house has seen its share of blood, horror, and the depths of the human soul. Cursed with sentience, it is destined to observe the terrors that lurk inside each and every one of us.

Isla lives alone in a large mansion deep in the woods. Isla has always lived here, though not always alone. Isla has a hunger: she likes to hunt, she likes to skin, and carve, and clean. Now Isla has hired the young Marie to help her keep the big house tidy, but Marie brings demons of her own into Isla's domain. And watching these two strange birds locked in a cage is the house itself, cursed with sentience, destined to watch the horror of the human drama unfold again and again.

What I truly adored about this book is that the protagonist isn’t human. Though the narrative follows Isla and Marie, the true main character is the house itself. The story is told from the house’s point of view, so you don’t access the characters’ thoughts and feelings––you only see their actions.

Without spoiling the story, I want to express that this is a story about women’s hunger and the way we as a collective society mythologize women. What’s interesting is that both Isla and Marie’s yearnings are palpable, though the house never blatantly tells us what they are. This is an interesting narrative device because it allows you as the reader to project onto them what it is you think they want. From what I gathered in reading, Isla wants a cure for her loneliness and wants to be seen as normal, despite how unusual she is. Meanwhile, Marie wants space and contentment, an escape from her abusive husband, and some meaning and purpose to her life.

It’s always the simplest desires that are the most elusive.

It’s also the simplest desires that people will do anything to get. Anything.

The sentient house tries to make sense of them both, but approaches Isla and Marie as though their actions are inevitable acts of human nature. It’s enough to make you wonder what traumas caused Isla to be the way she is and what the mansion witnessed before this particular story began. (There’s a brief section that compresses Isla’s first 18 years into a handful of panels. It’s a rough childhood.) The house articulates its understanding of Isla so poetically––the language is sparse and matter of fact; using an economy of words that strengthens the poetry of the descriptions. The horror element is scarcely seen in the writing itself but is ever-present in the art.

On the art: it’s remarkable. It’s all black, white, gray, and red. The style is somewhat like Edward Gorey meets watercolor. It’s engaging and every panel tells a story in and of itself. You could almost read the entire graphic novel with no words because the art itself is so vivid in its visual language, which means the poetically written element just adds all the more to the story.

The hunger element comes out so starkly in the art, though the mythologizing aspect is more metaphorical. Common myths around women include woman as martyr and woman as deceiver, and both of these tropes show themselves in these pages. It is easy to demonize both kinds of women (and so many more) because no matter what a woman does or doesn’t do, someone––including members of her own sex––takes issue with it. And so often, people are quick to judge women in those singular moments without considering what led up to them. It begs the question: Are we the worst things we have ever done? Put another way: Is the essence of who we are found in our lowest moments?

If we acknowledge that hurt people hurt people and that trauma begets trauma, we must also ask ourselves what lies at the heart of horror stories where the violence is enacted by and upon the body. These are the kinds of questions I see Graveneye asking and why I was compelled to keep reading. I also imagine that if I were to re-read Graveneye in a couple of years, I might have a totally different take on it. That’s the real magic of a book if you ask me––knowing it’ll hit you differently based on where you are in life.

If you’d like a copy of Graveneye––and I hope you do!––please use my Bookshop link. Doing so supports indie bookstores and this blog, and Bookshop is an Amazon alternative. So win-win all around!