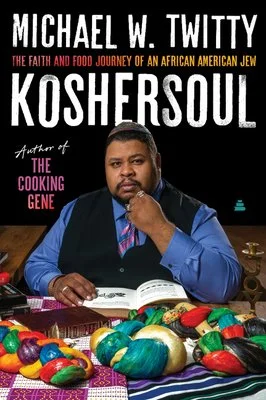

Hot Off the Shelf - Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew by Michael W. Twitty

[image description: The book cover of Koshersoul. The author, Michael W. Twitty, a Black man with a beard and mustache who’s wearing a blue shirt, black vest, pink striped tie and a yarmulke, is seated at wood table surrounded by rainbow challah bread and books in Hebrew. He’s looking at the camera with one hand under his chin.]

Disclaimer: I received a free copy of this book in exchange for an honest review. If you’d like a copy for yourself, there’s an affiliate link at the bottom of the page.

I love mixed-genre memoirs and memoirs exploring unexpected identities, and Koshersoul by Michael W. Twitty checks both of those boxes. Twitty is a chef who is also Southern, fat, Black, and Jewish, so the first 3/4 of Koshersoul is essays on the intersections of his identities and the last 1/4 is recipes for Black Southern Jewish cuisine.

First, the synopsis:

The James Beard award-winning author of the acclaimed The Cooking Gene explores the cultural crossroads of Jewish and African diaspora cuisine and issues of memory, identity, and food.

In Koshersoul, Michael W. Twitty considers the marriage of two of the most distinctive culinary cultures in the world today: the foods and traditions of the African Atlantic and the global Jewish diaspora. To Twitty, the creation of African-Jewish cooking is a conversation of migrations and a dialogue of diasporas offering a rich background for inventive recipes and the people who create them.

The question that most intrigues him is not just who makes the food, but how the food makes the people. Jews of Color are not outliers, Twitty contends, but significant and meaningful cultural creators in both Black and Jewish civilizations. Koshersoul also explores how food has shaped the journeys of numerous cooks, including Twitty's own passage to and within Judaism.

As intimate, thought-provoking, and profound as The Cooking Gene, this remarkable book teases the senses as it offers sustenance for the soul.

I totally understand the impetus to explore culture through food. I once had an overwhelming urge to make macaroni and cheese grape leaves in homage to my Southern and Palestinian identities, so blending culturally significant food traditions in a way that honors the cornucopia of identities of the person making the food makes sense to me.

Twitty is also probably one of the smartest non-academic writers out there. It’s so clear from reading his essays that he’s done an exorbitant amount of research and has interviewed other Black Jewish chefs and hobby cooks. The essays are intricately detailed, which is helpful in many cases but feels overwritten in others. For example, Twitty includes a ton of Yiddish words (and defines most of them for the non-Yiddish-speaking readers), and several times having the Yiddish word there makes sense and adds to the meaning of the essay. However, other times, it feels like an interruption in the train of thought and feels unnecessary.

Beyond the Yiddish vocabulary, Twitty clearly has a far-reaching vocabulary in his native English and isn’t shy about using uncommon words. Even though I consider myself fairly well-read, I had to pull out a dictionary a dozen or so times while reading Koshersoul. And, like some of the Yiddish words, the uncommon English vocabulary distracted from the story. The example that sticks out most in my mind is when Twitty used “frabjous” in a sentence, a word which means delightful, joyous, humorous and I thought to myself, Why the hell didn’t he just say that?!

In some ways, this book made me feel stupid, which I suppose is my problem, not his. However, I can’t help but wonder how many other readers felt the same way. This isn’t to say that Koshersoul isn’t quotable or that I didn’t find passages and sentences to enjoy. I dog-eared several pages (that weren’t recipes) that I plan to revisit.

Normally, my criteria for giving a book 5 stars is whether it’s quotable––specifically whether I felt compelled to underline passages. Since I did do that with this book, I should technically give it 5 stars, but there were some other issues that caused me to not love this book as much as I’d hoped I would.

The biggest issue for me is that while Twitty meticulously researched these food traditions for his essays, he doesn’t seem to discern what is traditionally Jewish cuisine from what foods are not traditionally Jewish cuisine but that are foods Jews on the whole like to eat. For example, challah bread is traditionally Jewish cuisine, but falafel––which is enjoyed by Jewish people but is also present in Palestinian, Lebanese, and other Levantine food traditions––does not belong to Jews in the same way challah does. I understand that the whole point is to blend the foodways of Southern African Americans and Jewish cuisine, but I chafe when one group claims a food for themselves that actually belongs to several other cultures. Obviously, Twitty and other Jewish folks are more than welcome to make falafel and enjoy eating it, but I don’t appreciate the insinuation that falafel belongs only, or primarily, to Jews.

The other issue, at least for me, is that so many of the essays are solely about Twitty experiencing racism in Jewish settings, such as the years he spent teaching at his temple. He caught racist flak from students, parents, other teachers, and rabbis. I think these essays are incredibly important and racism should always be brought to light, though what I felt was missing is why Twitty, who is a convert to Judaism, chose to stay in the religion after years of facing such rampant discrimination. It’s hard for me to wrap my mind around why someone would want to stay when they’re actively being discriminated against.

The essays don’t do the best job of explaining this––they mostly detail Twitty’s rebuttals to the racists and how these incidents have stuck with him over the years and what he wishes he could say to these people now, and ending with the explanation “Judaism is who I am and I’m just as Jewish as these racist white people,” but without exploring that further in this specific context. I would have loved to have heard more about why Judaism is so meaningful to him that he’s willing to endure the racism he encounters within it. Maybe I’m missing something, but I still don’t have a good sense of that. I almost feel like those essays need to be explored more fully in a separate book since, with a few exceptions, they don’t have to do with food.

It would be simplistic to say that the reason I didn’t love Koshersoul as much as I’d hoped is that I’m “not the target audience.” I’m not and I knew that going into it. I read a ton of books for which I’m not the target audience because it helps me learn from and understand other people and cultures that I might not ever be exposed to in real life. Koshersoul also feels like it’s written for people who are perhaps Jewish OR Black, but not always both, otherwise, Twitty wouldn’t have to explain his thinking so much in the essays; it would be a foregone conclusion if the target audience was solely people who are both Black and Jewish.

Overall, I’m glad this book exists and I hope it helps other Black Jews feel seen and represented. And, more than anything, I hope it helps people who don’t think Jews can or should be Black get an insight to what Twitty’s life is like and inspire them to become dedicated antiracist allies. Although I didn’t love Koshersoul as much as I’d hoped, I did learn a lot and I’d be open to reading Twitty’s other books.

If this sounds like a book you’d enjoy, I’d appreciate it if you bought your copy using my Bookshop link. Bookshop is an Amazon alternative that supports indie bookstores and blogs like mine.