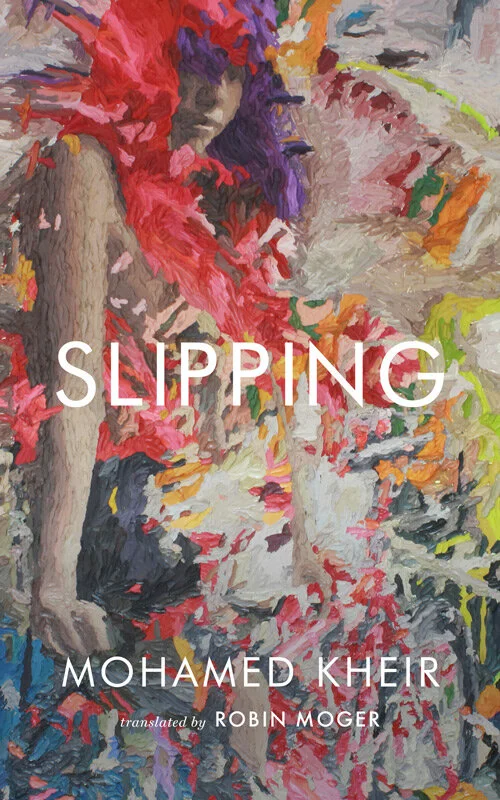

Hot Off the Shelf: Slipping by Mohamed Kheir

Disclaimer: I received a free copy of this book in exchange for an honest review and I honestly enjoyed it! I don’t write reviews for books I don’t like because that’s no fun. No spoilers are in this review.

Post contains an affiliate link.

“We all lost people in the revolution, one way or another: to death, to prison, to irreconcilable differences in the way we thought. But more importantly, we lost precious parts of ourselves, of our faith in life. This, I think, might be the pain that touches the reader of Slipping, for all that it touches him in the same dreamlike, hazy fashion that it occupies in the novel.”

–– Mohamed Kheir on writing through the Arab Spring

I’ve been wanting to read more translated books lately, especially books that have been translated from Arabic to English. I’ve finally realized that I’m probably going to be hopelessly monolingual for the rest of my life, so I might as well read all the books in Arabic that have been translated instead of holding out for my eventual fluency.

I got my hands on an early copy of Slipping by Mohamed Kheir. He’s an Egyptian author with several novels out, though this is his first one translated into English. Two Lines Press, which is through the Center for the Art of Translation, is really good about finding the gems in international literature and making sure they’re accessible to an English audience.

Before I dive in, the synopsis:

Under mysterious circumstances, Seif, a struggling journalist, is introduced to a source for a new story: a former exile with an encyclopedic knowledge of the country's obscure, magical spaces. Together--as tourist and guide--they step into a world hidden in plain sight.

In Alexandria, they wait as trains bear down on them at the intersection of several busy lines; they follow a set of stairs down to the edge of the Nile and cross the water on foot; and down south, they sit before a bare cave wall, a cinema of private visions. What begins as a fantastical excursion through a fractured nation quickly winds its way inward, as Seif begins to piece together the mysteries of his own past, including what happened to Alya, his girlfriend with the gift of singing sounds. Seif alone confronts the interconnectedness of his own traumas with Egypt's following the Arab Spring and its hallucinatory days of revolutionary potential.

Musical and parabolic, Slipping seeks nothing less than to accept the world in all its mystery. An innovative novel that searches for meaning within the haze of trauma, it generously portrays the overlooked miracles of everyday life, and attempts to reconcile past failures--both personal and societal--with a daunting future. Delicately translated from Arabic by Robin Moger, this is a profound introduction to the imagination of Mohamed Kheir, one of the most exciting writers working in Egypt today.

This is one of those cerebral novels that I feel like you need to read several times to really take it all in. That said, I’ve only read it once (so far) so this review is my first impression.

Slipping reads like a lucid dream in novel form. It’s clear that Seif recognizes the landscape he’s in, but everything is slightly off or just weird enough that you know it’s not entirely reality. The element of fascination, for me, is that the novel is set during the revolution, a time in which so many people in Egypt lost someone––either from death or irreconcilable political/ideological differences––that many people were existing in a cloud of grief and trauma. Anguish can distort reality. Anyone who’s ever suffered from severe depression (and I have) can attest to this. At different times I had visual and auditory hallucinations that I could have sworn to you were real. So even if the magical spaces and distorted reality were not objectively real in the landscape of the novel, it’s entirely believable that they were real to Seif.

There’s also a sense that these magical spaces are something of a maze, there one minute and gone the next. During the revolution, the literal landscape of the country was changing with bombs, fires, buildings being torn down, streets being blocked from military occupation, and the like. So it makes sense to me that the magical spaces that are central to the novel’s setting would appear and disappear suddenly. In Egypt during that time, one wouldn’t have known how permanent a safe, welcoming space would be and when one was destroyed or made inaccessible, another would have to be created in its place.

At the end of the book, there’s an interview with the author, Mohamed Kheir, and Robin Moger, the translator. where Kheir mentions that every surreal thing in the book is a riff on something that actually happened to him or someone he knows. He mentions a period where he could’ve sworn he saw the faces of his dead friends in crowds of people, for instance, and this plays out consistently throughout the novel. I find the magical aspects of the book even more fascinating knowing this because it shows that this fever dream haze is both a response to trauma and protection from it. It’s like the brain is going into safety mode to dull the impact of the otherwise debilitating trauma being experienced by living through a revolution in your backyard. The dreamlike state is the body trying to convince you what you’re seeing isn’t real so you can better manage seeing the horrors you’re faced with.

When I say the novel is cerebral, I don’t mean that it’s written in an arbitrarily academic way that feels designed to isolate readers or make them feel like they’re not smart enough to decipher the novel’s mysteries. I mean there’s an undeniable element of psychology and the novel reads like a psychological thriller cooked up by the subconscious. Can anyone adequately explain or even describe their dreams? Even the smartest and most articulate people struggle to do so. Yet this fleeting, ethereal grasp on events that toes the line between dream and reality is what the novel so brilliantly captures.

I feel like I’m still processing the novel and I’m going to be processing it for a long time. I will say that it’s a little difficult to keep some of the side characters straight at first, but the ending and Afterword make everything make sense and it’s a very satisfying payoff.

I will also say that I’ve read a number of translated books over the years and this is one of the best translated novels I’ve read in a long time, especially given the difficulty and nuance of the style and subject matter. There have been times when reading translated works that I felt a disconnect between the author and translator, like the translator wasn’t capturing what the author wanted to say very well. I gathered this from noticing how I’d be feeling one strong emotion from the text one moment and be totally confused about what was being said the next. I can’t imagine how challenging it must have been to translate Slipping, but I can tell you even without being able to read the original Arabic myself that Robin Moger did an excellent job.

If you’d like to buy a copy (and I hope you will), you can find Slipping by Mohamed Kheir at your favorite indie bookstore, from the publisher Two Lines Press, or online through my Bookshop link, which supports indie bookstores and my work on this blog.