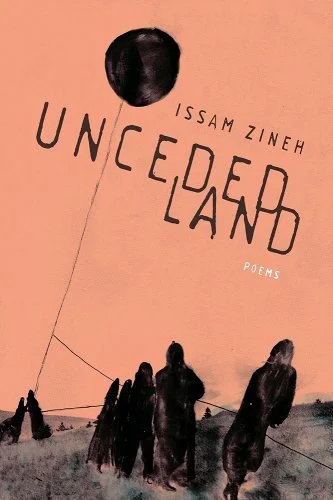

Hot Off the Shelf: Unceded Land by Issam Zineh

[image description: The book cover of Unceded Land by Issam Zineh. The background is a reddish-orange sky and in the foreground are several black-clad figures proceeding down a trail in the landscape. It’s an abstract painting that looks as though the figures are coming toward the viewer.]

I was given a free copy of this book in exchange for an honest review. If you’d like a copy for yourself, there’s an affiliate link at the bottom of this page.

This is a spoiler-free review; not that you can really spoil poetry.

It was a lucky day for me when poet and scientist Issam Zineh’s tweet about his debut poetry book, Unceded Land, appeared in my timeline. The algorithm must have me figured out because we weren’t following one another but I’m always eager to connect with other Palestinian and Palestinian-American writers. For once, I’m not mad about the robots and tech demigods stalking me.

I was immediately intrigued for several reasons, even beyond our shared heritage. But first, the synopsis:

Issam Zineh's debut collection Unceded Land is a lyrical marvel, tracing the lines of intimacy, loss, and colonial legacy. With an eye that wanders from the subtly beautiful to the crushingly blunt, his poetry seeks out the "primordial egg within us," the truths that are "traded in broken bones." Zineh's capturing of the romantic and violent, the personal and the political, is a testament to his unwavering dedication to plumbing the depths of emotion that lie in psychological and physical territories alike. Unceded Land bridges the gap between the mind and the world, daring the reader to journey further into its depths.

I was instantly drawn to the title. Often the phrase “unceded land” is used in reference to Indigenous people throughout North America who have been forced out of their ancestral homeland due to white greed, land theft, and genocide. Lately, I’ve been thinking about Indigenous people around the world, including Palestinians, who are native to Palestine and whose ancestral homeland is routinely stolen by Zionist settler colonialists.

In fact, when discussing Palestinian issues with people who may be unfamiliar with them, I often explain it like this: “You know how white people came to North America and started uprooting and killing Native Americans? That’s basically what Israel is doing to Palestine.” People tend to understand this explanation, which is why I so often default to it, though I’m not sure non-Palestinians conceptualize Palestinians as Indigenous in the same way. Yet I argue that we are: We have historically significant, meaningful culture traditions that are steeped in our ancestral land in much the same way Native Americans do. And when we are exiled from that homeland and living in the diaspora, it feels as though something is missing within us.

These are themes that appear in the poems in Unceded Land. The opening poems “Rare Bird,” “Catastrophic Sonnet,” and the title poem “Unceded Land” convey the diasporic struggle and ancestral memory with tenderness and care. And though these are important, it would be incorrect to say all the poems in the collection are about challenges relating to settler colonialism and genocide. Many poems are about love, divorce, and longing, or poems in response to other works of art.

I appreciate this because oftentimes Palestinians are reduced to our struggles and there’s a fixation on that which has been taken from us. While this is undoubtedly part of our identity and the lens through which we see the world, struggle is not all that we are. The poems in Unceded Land offer the full spectrum of human emotion, not just anger, sadness, and loss. These are valid, but so is our joy.

In fact, some of my favorite poems were about Palestinian identity beyond suffering. For example “Lexicon” is a meditation on words in Arabic, American Sign Language, and the prefix hyster-, which is derived from Greek. I was especially drawn to “What If a Love Like This,” which is a series of poems in the middle of the book where each new poem builds upon the last line of the one before, but taking it in a new direction; a reinterpretation if you will.

My favorite poem might surprise some people, just because it seems unlike the others in that it’s blunt. “Trigger Warning” surprised me, both in content, form, and language. It’s more of a prose poem than its purposefully lineated neighbors. The stanza that hooked me is

The term Middle Eastern is racist. I did not know that. I’m Middle Eastern. The correct term is SWANA. I also learned that from Twitter. Did you know that Middle Eastern has “colonial, Eurocentric, and Orientalist origins” and was created “to conflate, contain and dehumanize our people.”? I did not know that.

I actually had to look up what SWANA was because, like Issam, despite being Middle Eastern, no one has had previously bothered to inform me that “Middle Eastern” was racist. SWANA means Southwest Asian and North African. While not incorrect by any means, I wouldn’t go around telling other Middle Easterners/SWANA folk how they should or should not identify. I believe identity is deeply personal and people connect to different descriptors and terms for various reasons, so it’s not my place to “correct” people. I got the sense this is what Issam was getting at in “Trigger Warning” too.

My second favorite poem was “Catastrophic Sonnet,” which is about the Nakba and begins “My grandfather still has his house key from 1948.” I hope my grandfather still has his house key from when he left in the early 1950s, finding life under violent military occupation untenable for himself and his young bride.

Art, music, and classics lovers will also delight in Unceded land. Sappho, Pygmalion, Liriope, and Narcissus all make appearances. There’s a poem titled “Adagio” and another titled “Still Life With Oranges and Goblet of Wine,” a reference to the 1880s-1890s painting by John Frederick Peto. (I googled the painting, having never seen or heard of it previously, and I see why he was drawn to it.)

For all my rambling, I think the blurb from Ruth Awad on the back of Unceded Land says it best. And although I don’t often pay attention to blurbs, I know Ruth to have impeccable taste, so I trust her recommendations. After re-reading her blurb again upon finishing Unceded Land, she summed it up beautifully:

There’s a language for the space between worlds, and Issam Zineh’s stunning Unceded Land is it. It’s rare to encounter such a boundless lyrical voice that deftly leaps from the Nakba and colonialism—“how the wind whispers liberate”—to divorce and desire, but Zineh is part magician that way, never losing the thread. He undertakes the intricate work of naming the beautiful and the brutal around us, and what a lush music he’s made: “This coast will never say / ‘You have moved me.’ Children will be born. / Oranges will still grow without us.” Inventive, propelled by both the divine and the impossibly human, these poems are a profound and breathless truth.

–– Ruth Awad, author of Set to Music a Wildfire

I absolutely loved Unceded Land and it will forever have a special place in my heart and on my bookshelf. If you’d like a copy for yourself, I’d love it if you’d purchase through my Bookshop link. Bookshop is an Amazon alternative that supports indie bookstores, so it’s a win-win.