Why Reading Books That Make You Uncomfortable Makes You a Better Reader (And Person): Part 1

This is Part 1 of a three-part series exploring the value of reading books that make us uncomfortable and how we can grow from those reading experiences.

Being the recipient of an Alabama public schools education, I don't consider myself scientifically literate. On a good day, I can explain cell functions and the most basic laws of physics. On a good day, and they are rare. Most days, I can scarcely name chemical compounds beyond H2O and sodium chloride. I barely remember anything about why it was necessary for me to dissect fetal pigs and sheep eyeballs and cow brains. (I'm sure there was a point to be made somewhere.) This is not something I'm proud of.

I'm not proud of this because, as someone who places a high value on education, I feel that I've failed myself and succumbed to one of Alabama's many pervasive stereotypes. In my defense, an inordinate amount of time in my AP biology class was spent trying to convince my creationism-believing teacher to just please teach evolution because it was 35% of the AP exam. I lost that battle and scored only slightly better than the kids whose answers were quotes from Genesis.

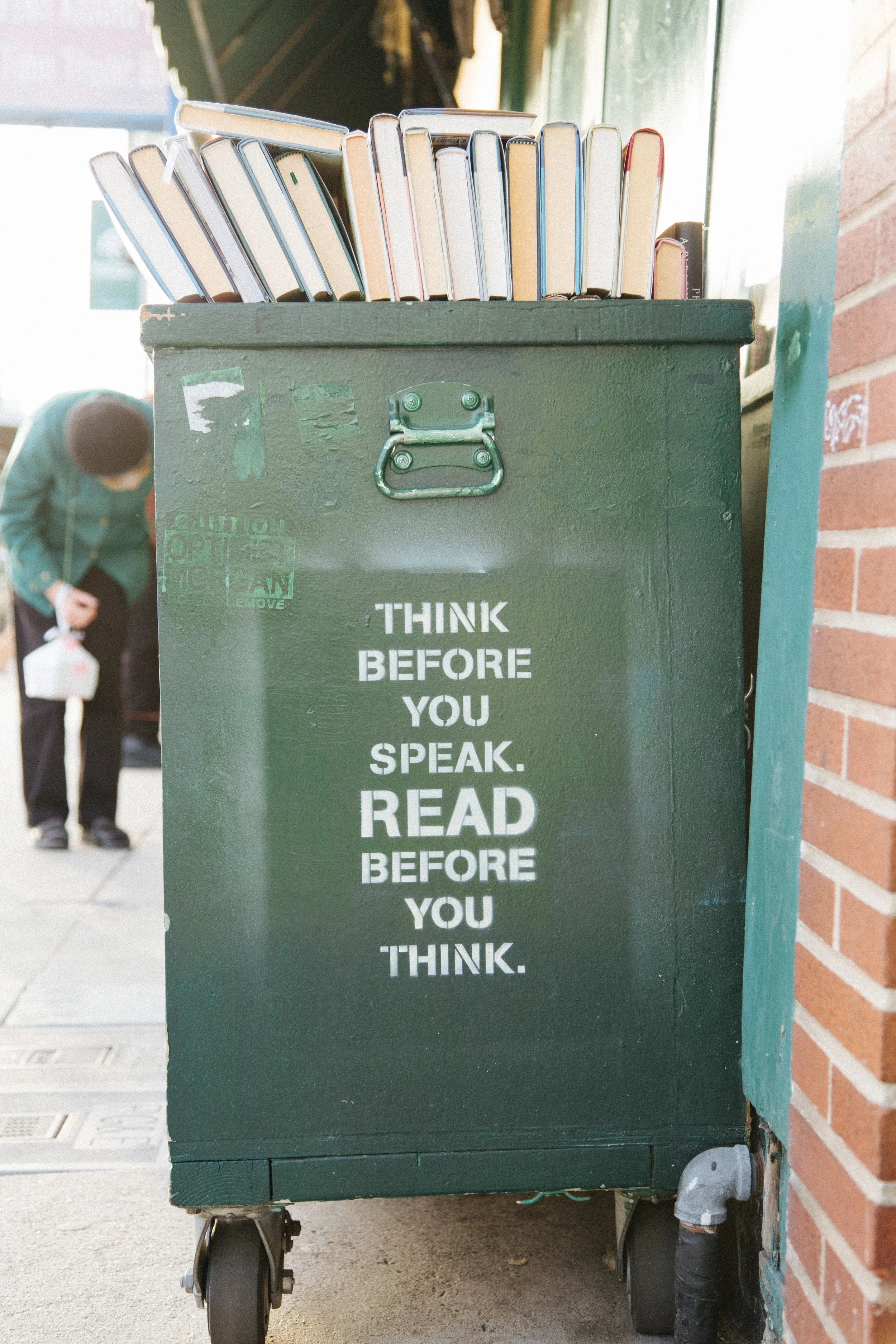

It's not surprising that I have little confidence in my ability to read and disseminate scientific literature, so I've stayed away from it. I feared that if someone saw me carrying a book about science---whether technical or more story-based---they'd strike up a conversation and realize I was not only a charlatan, but a fool. So although I know science is the law of universe, it makes me nervous. It feels beyond my grasp, beyond my ability to understand, and the ignorance I carry around as a result is uncomfortable.

I have always been afraid of people thinking I was stupid, but at some point in my post-college life, I realized that if I said nothing and stifled my natural curiosity, I'd never learn anything. I could either stew in my ignorance or overcome my fear. So I finally decided to try reading some science literature.

I started with Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach. I'd been told that she was a talented science writer who made scientific concepts approachable, interesting, and even funny. Stiff was all about the many things that can happen to bodies when they're donated to science. From crash test dummies, to surgical practice for medical students, to crime scene research, and more.

It's clear from Mary Roach's writing that she doesn't expect her audience to have a degree in biology. She's conscious of the fact that there are people like me in the world who probably don't know much about science, but would like to if you can tell us a good story.

Feeling more confident, I moved on to The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot. It's about the first immortal human cell line and all the medical research that was made possible from HeLa cells, as they were called. You also learn about the stickiness of medical research ethics since Henrietta's cells were taken without her knowledge and, despite making many scientists and businesspeople rich and famous, her family received no compensation.

Because the story follows Henrietta's daughter, who lived in rural Mississippi and didn't finish primary school, the reader is told the most basic facts in a way that doesn't make them feel like the author is condescending or dumbing down the text. As Deborah, Henrietta's daughter, learns about the research HeLa cells spawned, the reader is taken along for the ride. Rebecca Skloot isn't assuming the reader is scientifically illiterate---she's just reporting on Deborah's discoveries. And the story is made all the richer for it.

My confidence continued to grow. I could now have semi-intelligent conversations about dead bodies and HeLa cells. Although these are skills I might never actually need in the real world, I feel better having them. I feel better about myself, like maybe I can defy any negative Alabama stereotypes placed on me. Like maybe I can overcome my fear of people automatically assuming I'm ignorant based on where I was born.

Then I found Neil deGrasse Tyson, world famous astrophysicist and cosmologist. If I can understand dead bodies and HeLa cells, I can understand the origins of the universe, right?

I started reading his book Origins: Fourteen Billion Years of Cosmic Evolution. It's all about the origin of the universe, the Big Bang, matter, anti-matter, dark matter, Newtonian physics, some other science mumbo jumbo, and I hardly understood anything past the introduction. As I tried to push myself to keep reading, I felt those old feelings creep back in. I heard that inner voice judging me for not understanding concepts that, supposedly, I should already know.

In essence, the whole book is completely over my head. But just because I'm not ready for Neil deGrasse Tyson now doesn't mean I might not one day be. I'm still building up my confidence in my knowledge of science, so my more rational inner voice is telling me I just took a leap too far and too fast.

Even with this seemingly failed attempt at reading science lit, I'm still more confident now than I was when I began this journey. I'm still uncomfortable with science, but I'm more comfortable now than I've ever been. Learning, like reading, is a journey, not a destination. Despite how many steps i might try to skip, it's a journey all the same.

I haven't yet decided whether I'll continue with Origins, but I have decided that I'm not going to abandon my quest. As an independent adult, I can no longer blame the gaps in my public education's curriculum for my ignorance. It's up to me to fill those gaps, and I have to start somewhere if I'm going to fill them. Even if it makes me confront things I don't like about myself. Even if it makes me uncomfortable.